|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

History of the New York City Charter: 1898 - Present |

||

Fifty years ago, Brooklyn, amidst strong reservations, became a part of New York City. And while Brooklyn is legally one of the five boroughs comprising the Greater City of New York, there is still a feeling in Brooklyn that it is not and never will be anything except Brooklyn. Ask someone from Manhattan where he is from and he will say New York City. Ask someone from Brooklyn and he will tell you he is from Flatbush, or Red Hook, or Coney Island, Brooklyn, not from New York City. - Red Barber, Brooklyn Dodgers Broadcaster, 1949 - |

||

In 1898 two of the three largest cities in the United States, New York City and the City of Brooklyn merged into the “Greater City of New York” to prevent Chicago becoming the largest U.S. city and to provide Brooklyn with an abundant supply of fresh water from upstate New York. Approved by Brooklynites by just 247 votes, the merger set the framework for many of the great technology-based urban transitions of the new twentieth century, in transportation, in high-rise buildings, in new media, and in new energy forms. However, as a result of the merger, the various local identities within Brooklyn – and, in fact, Brooklyn itself – suffered big losses at the hands of outsiders that could no longer be controlled or directed. By 1958, sixty years after the merger and sixty years ago, Brooklyn (i) had lost control of much of its infrastructure to powerful city-wide agencies that ripped up neighbor-hoods for new roadways or housing projects and (ii) had suffered the loss of the valuable Brooklyn Dodger National League Baseball franchise launched in the City of Brooklyn in 1890. |

||

The contents of this Brooklyn Sports website open up new, all-local, economic development responses to the earlier (and on-going) losses suffered by Brooklynites. They do this by empowering the historical and famous identities that are still very much a part of life in the former City now Borough of Brooklyn today. Since 1976 the Charter of the City of New York has legally recognized eighteen Brooklyn Community Districts as the means of providing local control over city-wide service agencies like parks, police, sanitation, et al. The custom sportswear described on this web site links Brooklyn's historical, world-famous neighborhoods to these chartered Brooklyn Community Districts and to their currently operating Community Boards. The custom sportswear designs use the district maps, famous neighborhood names, local landmarks, and distinctive colors to promote, build, and empower eighteen separate district identities giving residents and businesses a sense of themselves as part of a distinctive and historical area of Brooklyn. |

||

Outside Challenges to Brooklyn Development |

||

Over the years the sort of technological opportunities and complex systems embodied in and supported by this Brooklyn Sports web site have generally been used by outside New York and national power structures to the detriment of Brooklyn residents and businesses. Through their mayor and political establishment, residents and businesses in the pre-merger 1890 City of Brooklyn controlled their finances, municipal services, land use decisions, and business development plans. Their City was also the home of a National League Baseball franchise. |

||

Merger with the City of New York |

||

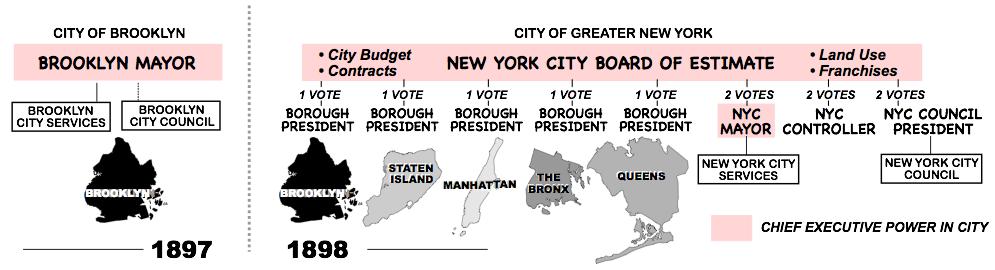

With the 1898 merger between Brooklyn and the City of New York the former City of Brooklyn became the new Borough of Brooklyn where its top elected official, the Borough President, exercised budgeting, land-use determination, public contracting, franchising, and other executive powers of the new Borough and the rest of the newly enlarged New York City as one of eleven votes on the NYC Board of Estimate. The merger also moved the administration of newly centralized city-wide services to the Mayor of New York City and created a new much larger City Council. |

||

|

||

MAYOR OF BROOKLYN BECOMES BROOKLYN BOROUGH PRESIDENT: 1898 |

||

Unfortunately, this arrangement was not good for Brooklyn businesses and residents. Just sixty years later, in 1958, following a period of great technological change – coal to oil, newsprint to radio and television, horse and buggy to automobile – large centralized city-wide service agencies like parks, housing, and transportation had taken charge of major portions of life in Brooklyn providing only occasional access to local interests through a crazy-quilt pattern of different local service districts under Mayoral control. |

||

Power Dynamics in Replacing Ebbets Field |

||

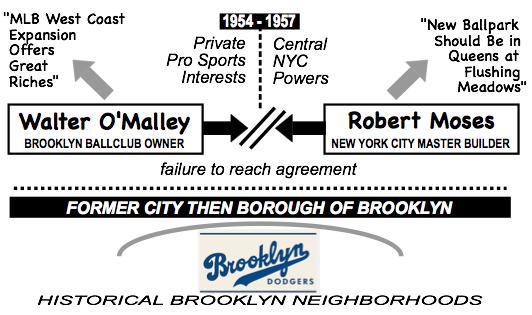

In that same year, 1958, the highly successful Brooklyn National League Baseball franchise left for Los Angeles helping that west coast city to move into the position of third largest U.S. city and separating Brooklyn from a share of the annual MLB revenue currently estimated to be $10 billion while extracting annual viewing and promotional payments from Brooklyn residents and businesses currently estimated to be $100 million per year. That such merger-related losses from central city-wide services and from private business interests were actually incurred by Brooklyn neighborhoods as well as by Brooklyn itself is easily demonstrated in the behavior and actions of two well-known 20th century people, Robert Moses and Walter O’Malley. These two controlling outsiders engaged in sham negotiations over building a replacement for Ebbets Field, the 40-year-old home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, where each was clearly motivated by non-Brooklyn objectives. |

||

|

||

DECISION-MAKING IN EBBETS FIELD REPLACEMENT |

||

During a twenty-year reign as NYC Parks Commissioner, Mr. Moses had developed a collection of external non-NYC funding sources and construction talent that, as successive elected city officials learned, put him in the driver’s seat with all NYC parks projects rather than the Mayor or the Board of Estimate. |

||

|

|||||

In transportation and housing work, Mr. Moses used “public authorities” to borrow money for municipal projects that even the NYC Board of Estimate could not control. In spite of vehement opposition from resi-dents, Mr. Moses ripped up neighborhoods along Third Avenue in Brooklyn for the Gowanus Expressway though Second Avenue was a less destructive option. When it came to replacing Ebbets Field, Mr. Moses was clear about his plans: the stadium would be built in Flushing Meadows in Queens even though that would make the Brooklyn Dodgers into the Queens Dodgers or the New York Dodgers. Mr. Moses had his way a few years later with the new New York Metropolitans (Mets). |

|||||

Robert Moses |

|||||

Mr. O’Malley came from a politically connected family and after graduating from Wharton Business School and Fordham Law, found a depression era job foreclosing on business mortgages for The Bankers Trust Company in Brooklyn that was headed by a family friend and former New York City Police Commissioner. Bankers Trust happened to be the Brooklyn Dodgers bank providing money for player acquisition and improvements to Ebbets Field. The bank also happened to be the administrator of the estate of Charles Ebbets after his death in 1927. Mr. O’Malley became the general counsel for the Dodgers and, over a period of ten years became sole owner of the Dodgers, acquiring the Ebbets' interest from the bank, buying out two other owners, and in 1950 forcing out the last remaining owner, Branch Rickey, the Dodger General Manager. |

||||||

|

||||||

Walter O'Malley |

||||||

By the mid-fifties it was clear to Mr. O’Malley that television revenues offered great riches and moving the Dodgers franchise to the west coast offered him the very best opportunity to cash in. Once in Los Angeles he was a primary force within in Major League Baseball expanding the number of MLB franchises from 16 in 10 cities (markets) to the current 30 franchises in 27 cities. |

||

NYC Charter Revisions in 1976 and 1989 |

||

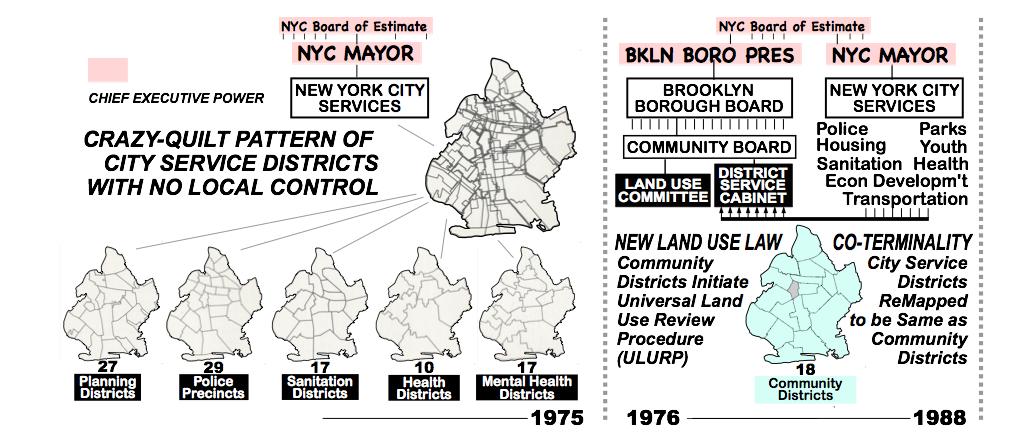

Brooklyn was not the only area of New York City to be abused by the power of well organized, well-financed, Moses-type centralized city services. In response, local district-based planning boards were established in Manhattan during the 1950s to set forth clear local priorities. By 1976 the New York City Charter was revised to give considerable power and funding to these local “community boards” throughout all of New York City. A new land-use process was also enacted into law giving these boards a key role in developing and approving all changes to land use and zoning. The most significant aspect of the 1976 charter revision was the requirement that central city services conform their service delivery district maps to the community district maps included in the charter. |

||

|

||

COMMUNITY DISTRICT POWERS IN 1976 CHARTER REVISION |

||

Called “coterminality,” this remapping of service districts meant that local community boards and their new full time District Managers were able to regularly review the performance of each city-wide service together with related services within the boundaries of their own district. Monthly meetings of a District Service Cabinet at each community board office became a required event for district officials of police, parks, sanitation, health planning, and other city-wide service agencies. A major step in decentralizing municipal operations in New York City, this 1976 revision to the NYC Charter returned, for the first time since 1898, a significant amount of executive power to Brooklyn: to the Borough President and to the staff and volunteer board members in each of the eighteen chartered Brooklyn Community Districts. Although franchises and certain city-wide contracts were not included in this decentralization; budgeting for city-wide services, land-use decisions, and views on a wide range of policies were developed and documented by individual Community Boards. These findings were combined at Borough Board meetings chaired by the Borough President who used this district input and one vote on the Board of Estimate in interactions with the Mayor. Although the Mayor had two votes, BOE executive decision-making involved eight other votes, one from each of the four other borough presidents and two votes apiece from the Controller and City Council President. This decentralized form of governance lasted just eight years until it was challenged in 1984. In a lawsuit captioned Board of Estimate v. Morris it was argued that the Board of Estimate was an unconstitutional government body because it violated the principle of “one man, one vote” since five borough presidents representing dramatically different numbers of people each had the same voting power. Four years later after a series of appeals, the United States Supreme Court agreed with this argument so the Board of Estimate, a key feature of the 1898 Brooklyn-NYC merger, had to go. |

||

|

||

ELIMINATION OF THE BOARD OF ESTIMATE IN THE 1989 CHARTER REVISION |

||

A new City Charter that conformed to the high court ruling by eliminating the Board of Estimate was quickly put in place in 1989. BOE powers on land-use, budgeting, franchises, and contracting were given to the City Council leaving the Borough President and the eighteen Brooklyn Community Boards with little more than an advisory role for decisions made by city-wide elected officials, agencies, and council-members. Other than a delegation of sixteen diverse council-members in a 51-member NYC Council, all chief executive powers of the former City now Borough of Brooklyn were removed from the Charter. The Brooklyn Borough President, the Brooklyn Borough Board, and each of the eighteen Brooklyn Community District Boards were completely excluded from NYC executive decision-making. The District Service Cabinets were allowed to remain but their power to actually fix any of the problems they uncover with city-wide services was limited to an advisory role. |

||

The Situation in Brooklyn Today: 2019 |

||

In a manner similar to removal by Dutch and English settlers of native-American Canarsie people from their Brooklyn lands, the new fully centralized mayor-council chief executive power in New York City allows moneyed outsiders to develop Brooklyn lands by driving out existing residents and businesses who are (i) unable to afford higher payments to outsiders in order to stay and who (ii) lack the political power in their community to prevent such development. This on-going 21st century bad deal for Brooklyn will continue until all-local development can again regain the upper hand against outsider direction and control. |

||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

NYC Charter Revision of 1976 |

||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Restorative Charter Revision by Public Initiative and Referendum |

||

NEW YORK CITY CHARTER REVSION PROJECT

Since 1989 NYC district boards have steadily lost the powers they got with their maps in 1976. The recent “Amazon Debacle” in Queens shows that the top-down development arrogance of Robert Moses that led to popular creation and empowerment of community boards and districts in 1976 is still operating in 2019. A charter revision by public initiative and referendum is needed to restore the lost powers of the Brooklyn Community District Boards and the Brooklyn Borough President.

It is useful to review the history of the New York City Charter and its role in how Brooklyn has been operated since its "grand merger" with the City of New York in 1898. Massive abuse by central city agencies during the first seven decades of the twentieth century resulted in a charter revision in 1976 that firmly established Brooklyn Community Districts (maps) and Boards (empowered community people) with real powers and budgets all under the direction of the Brooklyn Borough President, the position that replaced the Mayor of Brooklyn in the 1898 merger. These 1976 powers lasted just thirteen years until 1989 when the Board of Estimate that was the source of the Borough President's and Community Boards' powers was was undone (as unconstitutional) in a legal proceeding brought by Ronald Lauder and other development interests . . . a legal result that most likely violated the terms of the 1898 agreement that created greater New York City from the two cities of New York and Brooklyn.